“Collaboration between companies and research centres is beneficial for both parties, because it’s a source of technological ideas and possibilities and because it provides knowledge about what the market is looking for and what it needs.”

Francisco Carrión, PhD in Chemical Engineering from IQS-URL, Director of R&D and Analytical Development at Lebsa

The founders of Lebsa, Josep Maria Espinós and José Antonio Bofill, began their industrial activity at IQS nearly 70 years ago. The company’s relationship with the university has a long history.

Yes, we could say that Lebsa was founded through IQS years ago. Dr Espinós shared graduated with individuals such as Father Queralt, Dr Margarit, and Dr Condal and was close friends with Father Montagut. He was a professor at the university when he started setting up laboratories outside of IQS driven by his entrepreneurial spirit. He ended up setting up a laboratory with Father Queralt in the basement of the old Barça de Les Corts field. In 1951 he founded the company Laboratorios Espinós, a laboratory on calle Graus just a five-minute walk from IQS.

The company kept on growing, and ten years later, in 1961, it acquired land on what was then a vacant lot in Cornellá to increase production volume. Gradually, the company’s activities moved to the new facilities as the production of APIs continued to grow. In 2005 the plant was remodelled to become a modern GMP facility. At that time, Dr Espinós handed down the role of CEO his daughter Maria Luisa, but he continued his involvement with the company as its Chairman. Although the company had distanced itself in terms of its physical location from IQS due to its growing activity, he always felt very close to the university from which the company's roots originated. He always insisted on maintaining the connection between the two entities.

Dr Espinós passed away in 2012, but he continued coming to the company and thinking about chemistry up to his final days. He belonged to one of those legendary graduating classes in which the spirit of IQS was forged and he perfectly embodied that vision: unbridled passion for chemistry combined with a spirit of entrepreneurship and utilitas (usefulness) focused on business.

Could you tell us about Lebsa's current business activities?

Today, Lebsa is an SME with nearly 50 employees that is dedicated to developing and manufacturing generic APIs. The company exports over 85% of its production, reaching every continent.

The Espinós family, which owns the business, has decided to invest in the company to take another leap forward in growth. The new building with laboratories and offices reflects this commitment, as well as the expansion of the R&D department that is currently home to more than 10 researchers.

Our goal for the next few years is to incorporate new products into our portfolio and position ourselves as an innovative and sustainable company. We expect Flow Chemistry will play an important role here.

Do you think universities like IQS are necessary for promoting research, development, and technology transfer?

I think they’re essential. Most companies in our sector dedicate a rather small amount of their budgets to basic science. If you think about the short term, with market pressure deadlines and costs, science can seem like an investment that is hard to justify. Basic science research requires longer periods of time for its results to be applied to industry.

However, companies need these new discoveries and technologies that allow us to be more competitive. And this is where universities like IQS come into play, where you can work on this type of cutting-edge research.

That's why collaboration between companies and research centres is beneficial for both parties. For companies, it's a source of technological ideas and possibilities. And for research centres, collaboration with businesses gives them knowledge about what the market is looking for and pushes them to find applications to satisfy these needs.

Our country boasts many scientific publications. However, that doesn't show in the number of patents or cutting-edge technology companies. Greater collaboration between universities and companies would help translate this knowledge into practice.

You decided to begin your step towards Flow Chemistry with an Industrial Doctorate at IQS. What is your opinion on this type of collaboration?

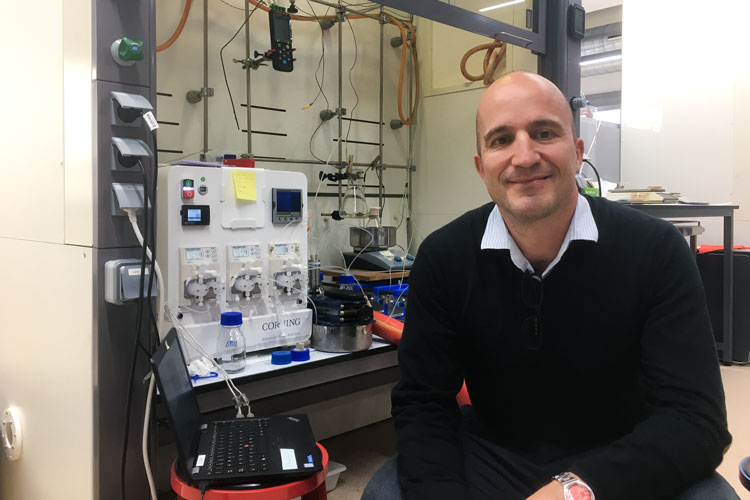

Really, it all started a long time ago. During a conversation with Dr Julià Sempere about seven years ago, he asked me whether we had considered Flow Chemistry as an option. At the time I already had many projects underway, so that was where the conversation ended. Years later when I started working at Lebsa, the topic of Flow Chemistry came up during a brainstorming session on how to compete with companies in China and India. I thought back to the conversation we had years ago and we contacted Dr Sempere to see how we could collaborate.

The project we were considering involved applying Flow Chemistry to an existing process. Obviously, this implied a considerable amount of time and a new technology completely unknown at Lebsa, its application to a process, and its transfer to an industrial level. For this type of collaboration, the three-year industrial doctorate option seemed most appropriate.

Our experience could hardly have been better: The person who was hired for the doctorate, Bea Ravasio, is doing a spectacular job and we want her to remain on Lebsa's staff when she finishes her PhD.

In addition to this personal aspect, there's also the more pragmatic issue of return on investment. The contributions and improvements that Bea made in the first year and a half have already made the investment in the PhD programme incredibly profitable. Like I said, we couldn't be happier.

Now that Lebsa has made a major commitment to Flow Chemistry and already has its own development laboratory, what do you expect from this important step? Will you implement it in your production soon?

Not only have we acquired the equipment to work in the laboratory, but we have also collaborated with more research centres that are specialised in Flow Chemistry and we have attended conferences as well. We're learning a lot, mainly from mistakes. We've had processes that have worked really well in the laboratory, but when we ran the numbers to move on to an industrial plant to manufacture by the tonne, they've proven to be unfeasible due to operational and logistical issues.

However, we now have a couple of processes that could be transferred to an industrial scale. The problem we face is how to get to the factory in a phased manner. We want to start with a process that doesn't involve excessive investment, that allows us to gain experience and confidence with technology at an industrial level, and, logically, that doing it continuously is an advantage compared to the batch process. It can be difficult to find a process that meets these requirements, but choosing it correctly is critical as it will shape the future of the technology's implementation in the company. Fortunately we have a process that appears to meet these conditions.

Finally, do you think flow chemistry will be the fine chemistry revolution?

It's a great tool that makes it possible to achieve extreme pressure and temperature reaction conditions in a safe and sustainable way, as well as improvements in product performance and quality. But it has limitations. The main one is, broadly speaking, that you have to work with liquids and the vast majority of APIs and their intermediates are solid.

Will flow chemistry replace batch chemistry? I don’t think so. There are batch reactions and operations that work very well in a cost-effective and safe way. It would be hard to justify doing them continuously at an industrial level. Will it allow access to reactions that are impossible in batch? Of course, and that's sufficient for being able to apply that competitive extra at a company. It’s not necessary to do all the steps of chemical synthesis in flow chemistry. If you manage to make one using flow chemistry that’s impossible in batch chemistry or one that’s much more efficient in flow chemistry, then you’ve already set yourself apart from the competition. And that really is disruptive, a real revolution.